Where Should the Money Come From?

Key Findings

- The fiscal responses to the COVID-19 pandemic will require policymakers to consider what revenue resources should be used to fill budget gaps.

- Tax policy experts have proposed wealth taxes, (global) corporate minimum taxes, excess profits taxes, and digital taxes as opportunities for governments to raise new revenues.

- Instead of designing novel taxes, however, governments should focus on neutral and competitive reforms to existing taxes for sustainable financing and to support economic growth.

Introduction

The pandemic has led governments across the world to increase spending quickly and in dramatic ways. Initial tax policy responses from Germany, the U.S., and the UK amounted to more than 3 percent of GDP.[1] Those countries and others have moved on from the initial response to longer-lasting fiscal support measures, with both Germany and the UK relying on temporary VAT reductions to provide relief.[2],[3] France and Greece are exploring tax cuts that would provide relief to businesses (in the case of France) and benefits to individuals looking to relocate (in the case of Greece).[4],[5]

In response to the sizable budget deficits that countries are incurring, some policymakers are already considering what revenue sources will provide the funds to pay down the bill from the pandemic. While the middle of a pandemic is not the time to hike taxes, governments should begin considering how to sustainably finance the current deficit spending once the crisis recedes.

The tax policy community is not short on ideas, but governments are already showing their cards in what they may or may not be interested in changing for the short or the long term.

A general framework to analyze options for raising revenues should pay attention to the capacity of a tax to raise revenue in a weak economic situation, and the burden the tax would place on economic recovery (both on demand and supply through higher taxes on consumption, or alternatively business investment and hiring).

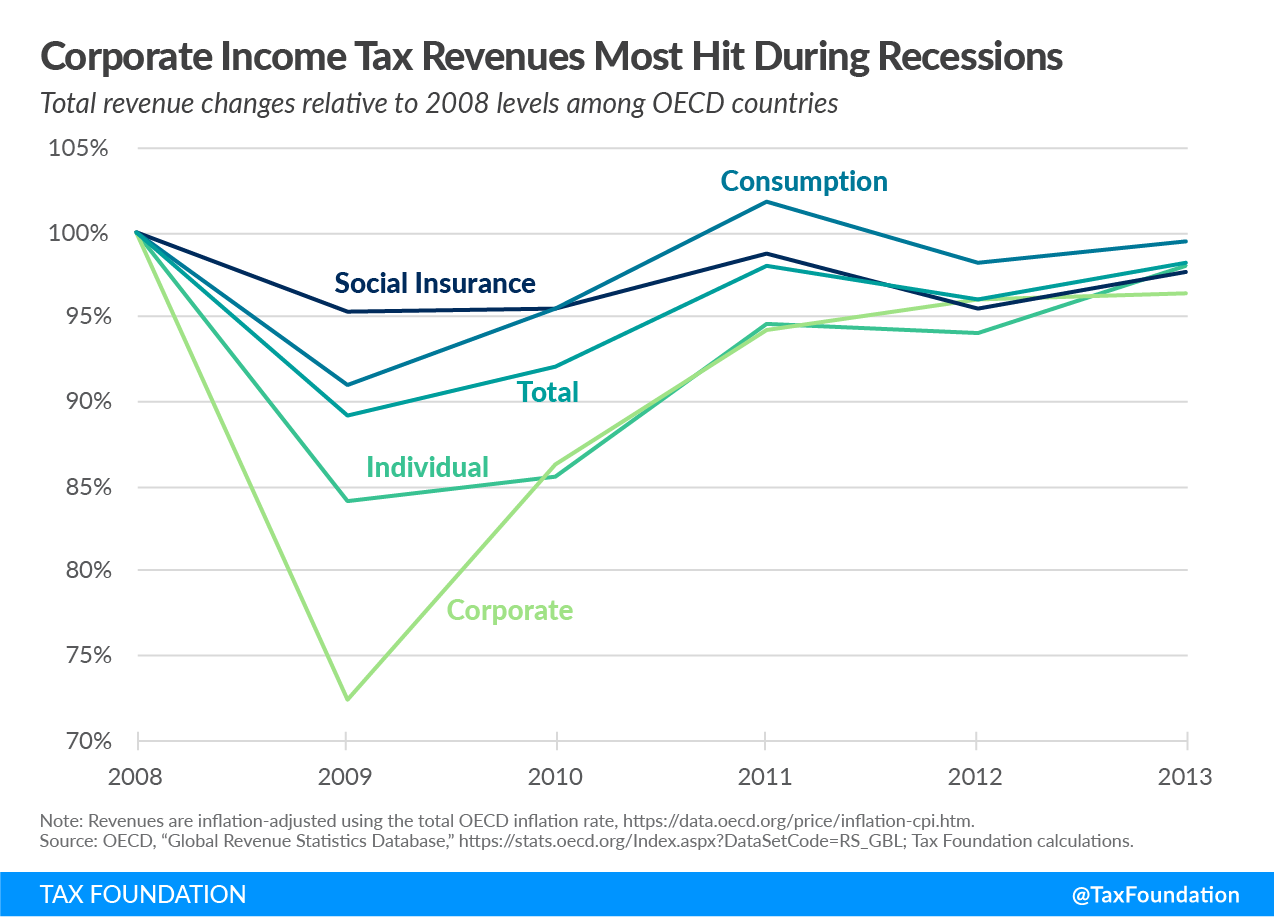

The recession in 2009 provides some clues to how revenues change in an economic downturn. Income taxes (both corporate and individual) took much longer to recover and were impacted more severely than consumption taxes and taxes that fund social insurance programs.[6] By 2013, only consumption tax revenues had regained their previous level (albeit only for 2011).

Unfortunately, the current recession will likely be deeper than the Great Recession. The OECD has forecast two scenarios for GDP—one which accounts for a second wave of infections and a related second economic shutdown, and another in which that second outbreak is avoided. Both scenarios anticipate a sharper downturn in economic activity than occurred among OECD countries in 2009. In 2009, OECD economies shrank 3.3 percent and grew at a rate of 3 percent in 2010. The OECD expects economies to contract by 7.5 percent to 9.3 percent in 2020 and rebound with growth rates between 2.2 percent and 4.8 percent in 2021.

Following the initial response of short-term fiscal relief, tax policy faces the challenge of responding to the crisis with measures that fill budget gaps in the long run while maintaining or improving competitiveness for investment and growth. This paper reviews some recent policy proposals including wealth taxes, minimum taxes, excess profits taxes, consumption taxes, and digital taxes.

Taxes designed with neutrality and competitiveness in mind can both fill budget gaps and support an economic recovery.

Taxes on Wealth?

Early on in the crisis, Camille Landais, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman recommended a progressive wealth tax to fund the European response to the pandemic.[7] They estimate such a tax could raise 1 percent of EU GDP in revenues each year. They link their proposal to hypothetical EU debt issuance of 10 percent of EU GDP; the European Council recently adopted a borrowing plan of 5.4 percent of EU GDP.[8]

Contrary to this recommendation, however, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire panned the idea of bringing back the French wealth tax that was abandoned in 2018.[9] Additionally, Norway (although not an EU country for purposes of the Landais et al. proposal) recognized the need to adjust its wealth tax during the crisis.[10] The government temporarily postponed wealth tax payments to avoid having businesses that are running losses pay out dividends to their shareholders to cover wealth tax liability. On the other hand, Peru is exploring a wealth tax as a new revenue source, although a former economy minister is already questioning the policy’s potential to raise revenue.[11]

In 2017, France and Spain raised just 0.22 percent and 0.18 percent of GDP in net wealth tax revenue.[12]

While many countries could likely benefit from improvements to their property tax systems, wealth taxes will directly impact capital formation, which could impede the economic recovery that countries hope to see once the pandemic recedes.

Global Corporate Minimum Taxes?

Policymakers and tax experts are also looking at a variety of corporate tax proposals that are focused on large, multinational companies. The OECD is working on a proposal to implement a global corporate minimum tax, and a blueprint of that policy is expected in October of this year.

Initial OECD analysis suggested that a minimum tax with a 12.5 percent minimum rate could generate up to $100 billion annually in revenues for countries across the globe.[13] However, those revenues would not be distributed evenly, and the estimate is based both on assumptions about how the policy would work and on data that predates other similar policies, which both have implications for how much any one country could gain from the policy.

The OECD estimated that, on average, countries could gain an extra 3 to 4 percent of corporate income tax revenues. Across the OECD, though, corporate income tax revenues make up 9.5 percent of total revenues.[14] While different regions of the world rely on corporate income taxes to varying extents, the ultimate impact of a global minimum tax may not be as large of a fiscal benefit as some might otherwise expect.

As an example, in 2018 Germany raised 5.6 percent of its €1.3 trillion in total revenues through corporate income taxes. If Germany were to gain an extra 4 percent of corporate income tax revenues from the OECD proposals, that would result in an additional €3 billion per year. Of course, Germany could be an outlier in gaining revenue from a global minimum tax, but it is worth pointing out that the supplementary budgets passed by the German government in response to the pandemic totaled €230 billion.[15] Looking to a global minimum tax to offset that level of spending increase seems to miss the difference in scale of the cost versus the revenue option.

The OECD approach raises questions about what the point of the project is—is it simply to raise revenue, or is it to design a better tax system? As Michael Devereux recently said, the overall OECD effort (Pillar 1 and Pillar 2) seems to be based on a principle of “Taxing multinationals’ profits pretty much everywhere we can think of. Just in case.”[16] But even with an all-of-the-above tax approach to multinationals, it is questionable whether the revenue will be a significant contributor to finance the deficits that are currently being accumulated or if it will simply be another layer of complexity in the international tax system.

A separate variant of the global minimum tax has been recommended by Kimberly Clausing, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman.[17] They recognize the global trend in lower corporate tax rates and offer a proposal that would seriously change how countries treat income earned in foreign locations. They use the concept of a tax deficit, defined where a company has a foreign effective tax rate below a country’s minimum rate; the difference between the minimum rate and the foreign effective rate is the deficit. For instance, if the U.S. were to apply a 21 percent minimum tax rate, and a company had a foreign effective tax rate of 5 percent, the U.S. would be able to tax the difference between the 5 percent and 21 percent rates to collect the “tax deficit.” Their analysis suggests that such a policy could generate upwards of $400 billion in tax revenue for the U.S. over the next 10 years.

One problem with a minimum tax of that sort is it would directly raise the cost of capital and thus impact business investment decisions just at a time when countries will be clamoring for investment and growth. Minimum tax proponents tend to focus on the potential revenue benefits without recognizing the potential costs in the form of lower output over the longer-term. Governments will need to take both sides into account as they face larger deficits and a significant hole in economic output.

Excess Profits Taxes?

Another policy that has been suggested separately by Reuven Avi-Yonah, and Tarcisio Diniz Magalhaes and Allison Christians, is an excess profits tax.[18],[19] The idea is to design a separate tax that taxes companies with high profit margins (above a threshold deemed excessive) at a higher rate. While Avi-Yonah makes a recommendation for a U.S. excess profits tax, Magalhaes and Christians advocate for a global excess profits tax that is built on country-by-country reports.

Generally, these proposals harken back to policies that were adopted decades ago as ways to finance the war effort. My colleague Scott Hodge recently pointed to Tax Foundation research from 1950 that shows how harmful those policies are.[20]

The real challenge of any excess profits tax, and one that Christians recently noted in a presentation, is defining what is excessive.[21] As U.S. Treasury Secretary Fred Vinson noted in the 1940s,

“The difficulty is that calling profits excessive does not make them excessive. Calling profits normal does not make them normal. Normal profits and excessive profits look alike. There is no chemical reagent to distinguish them. The excess-profits tax, to be sure, has a formula—a very complicated formula in its entirety—for distinguishing normal and excessive profits. But that formula is seriously defective.” [22]

The definition of excess or normal profits does not need to be quite so challenging. As my colleague Erica York puts it,

“The normal return to capital is the amount required for an investor to break-even on an investment, enough to cover the cost of her investment without being any better off. The supernormal return to capital, on the other hand, is the amount above and beyond the normal return and represents an increase in the investor’s welfare. Supernormal returns to capital may arise due to monopoly power, economic rents, innovations, or the return to risk—and firms often earn at least some above the normal return to capital when they make an investment. Under a neutral tax code, the normal return to capital would be exempt from tax (as it does not represent an increase in welfare), while the supernormal return to capital would be subject to tax.”[23]

How does one arrive at such a system that only taxes excess or supernormal returns? Policy can exempt the normal return from taxation through full deductions of input costs, losses, and capital costs, resulting in a so-called cash-flow tax.[24] Some small countries, including Estonia, Latvia, and Georgia, have corporate taxes that work like that by only taxing profits that are distributed to shareholders.[25],[26]

Instead of layering on a new definition of excess profit onto existing tax systems and applying a separate rate to profits that are deemed to be excessive, policymakers should evaluate whether their current tax policies are well-designed to tax economic profits. Jason Furman of Harvard University and the Peterson Institute for International Economics has proposed reforms that could lead to such a system in the U.S.[27]

A system that only taxes excess profits as they arise rather than use a formula to define, from the top down, what excess profitability means would be better for growth and revenues over the long run. This does not necessarily mean that a corporate cash-flow tax as in Latvia, Georgia, and Estonia would raise more revenue than a more standard corporate tax paired with an excess profits tax. It does show, however, that before adopting an excess profits tax, policymakers should evaluate whether the existing corporate tax base is, or is not, well-suited to taxing excess profits.

Consumption Taxes?

The backbone of many tax systems around the world is a consumption tax. In 2018, consumption taxes made up nearly one-third of revenues in OECD countries on average.[28] Common among many OECD countries is the value-added tax, or VAT, which is an indirect tax on consumption. Tax revenues from consumption are generally more stable than income tax revenues, even during economic downturns.[29] However, VAT design can significantly influence whether tax revenues will rebound because consumption patterns could shift from goods that are taxable to goods that are taxed at a lower rate or are exempt from VAT.[30]

In recent months, several countries have reduced VAT rates and provided exemptions for goods and services connected to the effort to address the pandemic. Temporary VAT cuts have been adopted by Germany and the UK.[31],[32]

With such a large portion of government revenues coming from VAT, policymakers should consider ways to shore up this revenue source for the long run. The EU annually measures the VAT Gap which reflects the difference between expected VAT revenues and revenues collected.[33] That difference could be due to fraud, evasion, avoidance, or bankruptcies. In 2017, the EU VAT Gap was measured to be €137.5 billion.

VAT has been changing in recent years to account for the digitalization of the economy. Changes to VAT that incorporate online goods and services have resulted in higher revenues for many countries. The EU raised an additional €14.8 billion of VAT revenues in the first four years after implementing measures to include cross-border trade in digital goods and services in VAT.[34]

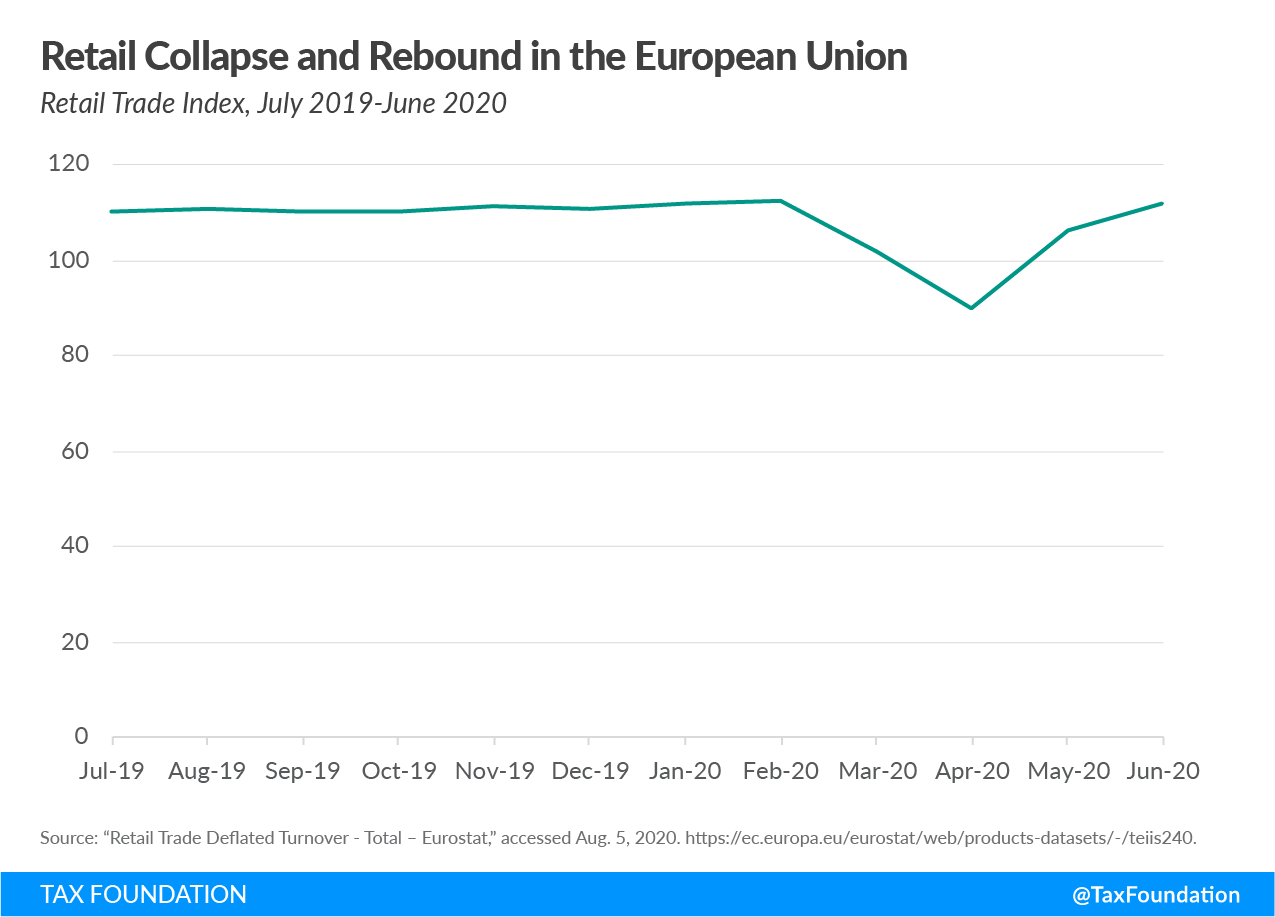

As consumption rebounds in the wake of the pandemic, policymakers should ensure that their consumption tax systems are well-designed. In Europe, that rebound is already occurring, although whether it will be a sustained rebound is uncertain. While retail trade in the European Union collapsed 32 percent from February to April, that was followed by a rebound in the following two months of similar magnitude.

Consumption taxes revenues could therefore be quick to recover even as incomes remain suppressed. However, VAT policies with significant gaps or reduced rates will continue to be hindered in their ability to raise revenue.[35]

Digital Taxes?

Countries have also looked to digital taxes as a way to bring in new revenue recently.[36] Though digital taxes come in various forms, one important variant is the Digital Services Tax (DST).

DSTs are revenue-based taxes that are aimed at certain large, multinational businesses and operate like tariffs on digital services. Two examples are the French and UK DSTs. The French policy was adopted in 2019, and the UK followed in 2020. Although the legislative efforts on these proposals predated the pandemic, policymakers have suggested that the reliance on virtual platforms throughout the crisis has increased the justification for special taxes on digital companies.[37]

However, these taxes are both distortive and expected to raise relatively little revenue. The distortions arise through the DST structure—a selective tax on gross revenues. Even a low statutory tax rate can result in a high effective tax rate on businesses with low profit margins. The selective approach arises in the fact that DSTs are targeted only at large, digital companies.

For all the effort, the resulting revenue tends to be small. A recent IMF paper finds that among five European proposals for digital services taxes, all are expected to raise less than 1 percent of GDP annually.[38]

In addition to raising relatively little revenue, DSTs have the potential to spark a trade war. The United States has threatened France with 25 percent tariffs on $1.3 billion worth of trade in response to the French DST.[39] Those tariffs would not take effect until 2021, however.

The European Union’s new budget plans also envision a digital tax, although it is unclear what form that tax will take.[40]

Evaluating Current Revenue Sources

So far, most of the discussion has been about proposals on new revenue sources in connection with the eventual budget demands from the crisis response and economic collapse. However, countries need not focus on novel approaches to close budget gaps. The real challenge will likely be more boring. Countries will need to spend time reviewing how their tax bases are designed. If significant portions of consumption are excluded from a country’s VAT base or subject to a reduced rate, a rebound in consumption activity will not be fully reflected in revenues. A rebound in consumption of exempt goods will, by definition, not contribute to a rebound in consumption tax revenues. As an example, the UK VAT covers just 45 percent of final consumption.[41] Even apart from the challenges of financing the fiscal response to the pandemic, the UK should consider improving its VAT by broadening the tax base.

Countries should also review tax preferences that can be costly in terms of tax revenues. These can take the form of patent boxes, and preferences for particular industries.

At the same time, the pandemic should provide policymakers with an incentive to review taxes that stand in the way of recovery and growth. In France, the government is exploring a €20 billion (US $22.4 billion) tax cut for businesses over the course of 2021 and 2022. France has a system of production taxes that can account for the majority of taxes some companies pay even beyond corporate taxes.[42] These taxes include both taxes based on value-added and on turnover.[43]

Turnover taxes are particularly harmful to productivity because they cause a cascading effect throughout the economy by applying at each stage of production. Unlike a VAT, however, turnover taxes are not credited back at each stage. Instead, the tax costs pile up, harming investment and productivity.

Policymakers will need to think creatively about improving their tax systems to cope with the budget needs in future years, but they will likely be better served by modifying existing revenue sources rather than building new systems from scratch.

Conclusion

Governments should be hesitant to raise taxes at the current moment.[44] However, the fiscal response to the current crisis will require some creative thinking on how to sustainably finance the new debt that governments are incurring.

While many tax proposals suggest new and innovative tools for raising revenue, governments should focus on reforming current revenue sources before expanding their tax toolkits. Consumption tax revenues will likely rebound first, although that rebound will be hindered by countries’ own policies that exclude large swaths of consumption from taxation. Corporate income taxes should be reformed with an eye toward supporting business investment and hiring.

Tax policies that constrain investment and hiring will increase the long-term economic risks from the pandemic by weakening an eventual recovery. Tax policy will be a tool that governments look to in supporting the recovery both in public finances and growth. Balancing those priorities is possible, and governments should look to neutral and competitive policies to meet their goals.

[1] “Tax and Fiscal Policy in Response to the Coronavirus Crisis: Strengthening Confidence and Resilience,” OECD, May 19, 2020, https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=128_128575-o6raktc0aa&title=Tax-and-Fiscal-Policy-in-Response-to-the-Coronavirus-Crisis.

[2] Daniel Bunn, “Germany Adopts a Temporary VAT Cut,” Tax Foundation, June 16, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/germany-temporary-vat-rates-cut/.

[3] “Guidance on the Temporary Reduced Rate of VAT for Hospitality, Holiday Accommodation and Attractions,” HMRC, July 9, 2020, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/revenue-and-customs-brief-10-2020-temporary-reduced-rate-of-vat-for-hospitality-holiday-accommodation-and-attractions/guidance-on-the-temporary-reduced-rate-of-vat-for-hospitality-holiday-accommodation-and-attractions.

[4] “France to Cut Business Taxes by 20 Billion Euros over Two Years,” Reuters, July 15, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-economy-tax-idUSKCN24G2UH.

[5] Sarah Paez, “Greek Government Proposes Tax Incentives to Spur Growth,” Tax Analysts, July 27, 2020, https://www.taxnotes.com/tax-notes-international/tax-preference-items-and-incentives/greek-government-proposes-tax-incentives-spur-growth/2020/07/27/2cr7j.

[6] Daniel Bunn, “Tax Policy and Economic Downturns,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 18, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/government-revenue-most-hit-recession/.

[7] Camille Landais, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “A Progressive European Wealth Tax to Fund the European COVID Response,” VoxEU.Org, Apr. 3, 2020, https://voxeu.org/article/progressive-european-wealth-tax-fund-european-covid-response.

[8] Daniel Bunn, “The New EU Budget Is Light on Details of Tax Proposals,” Tax Foundation, July 22, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/new-eu-budget-is-light-on-details-of-tax-proposals/.

[9] “Reimposing French ‘ISF’ Wealth Tax Would Be Bad Idea -Le Maire,” Reuters, May 18, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-idUSFWN2CZ028.

[10] Daniel Bunn, “Norway Opens the Fiscal Toolbox In Response to COVID-19,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 24, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/norway-coronavirus-relief-wealth-tax-vat/.

[11] A. Kristina Zvinys, “Peruvian ‘Solidarity Tax’ Unlikely to Offset Deficit Spending,” Tax Foundation, July 10, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/peru-solidarity-tax-wealth-tax/.

[12] “Global Revenue Statistics Database,” OECD, accessed Aug. 5, 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=RS_GBL.

[13] Elke Asen, “The OECD’s Impact Assessment on Pillar 1 and Pillar 2,” Tax Foundation, Mar. 17, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/summary-of-the-oecd-impact-assessment-on-pillar-1-and-pillar-2/.

[14] Cristina Enache, “Sources of Government Revenue in the OECD,” Tax Foundation, Feb. 19, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/publications/sources-of-government-revenue-in-the-oecd/.

[15] “Policy Responses to COVID19,” IMF, July 31, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Topics/imf-and-covid19/Policy-Responses-to-COVID-19.

[16] “Indiana/Leeds Summer Tax Workshop Series: Michael Devereux (Oxford University),” July 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDnwLklT0gM&feature=youtu.be&t=704.

[17] Kimberly A. Clausing, Emmanuel Saez, and Gabriel Zucman, “Ending Corporate Tax Avoidance and Tax Competition: A Plan to Collect the Tax Deficit of Multinationals,” Social Science Research Network, July 19, 2020, https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3655850.

[18] Reuven Avi-Yonah, “It’s Time to Revive the Excess Profits Tax,” The American Prospect, Mar. 27, 2020, https://prospect.org/api/content/453ef10e-6fda-11ea-8ddc-1244d5f7c7c6/.

[19] Tarcisio Diniz Magalhaes and Allison Christians, “Rethinking Tax for the Digital Economy After COVID-19,” Social Science Research Network, June 26, 2020, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3635907.

[20] Scott A. Hodge, “The History of Excess Profits Taxes Not as Effective or Harmless as Today’s Advocates Portray,” Tax Foundation, July 22, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/excess-profits-tax-pandemic-profits-tax/.

[21] “Indiana/Leeds Summer Tax Workshop Series: Allison Christians (McGill University),” July 2, 2020, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iwJcmZaWFow.

[22] “Financing Defense: Is An Excess Profits Tax the Solution?,” Tax Foundation, Dec. 1, 1950, https://taxfoundation.org/financing-defense-excess-profits-tax-solution/.

[23] Erica York, “Reviewing the Benefits of Full Expensing for the Post-Pandemic Economic Recovery,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 27, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/benefits-of-full-immediate-expensing/.

[24] For an example of how to transform a corporate and individual income tax system to this type of cash-flow tax, see Joel Slemrod, “Deconstructing the Income Tax,” The American Economic Review 87:2 (May 1997): 151–55.

[25] Daniel Bunn, “Better than the Rest,” Tax Foundation, Oct. 9, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/estonia-tax-system-latvia-tax-system/.

[26] Gia Jandieri, “Tax Reforms in Georgia, 2004-2012,” Tax Foundation, July 17, 2019, https://taxfoundation.org/tax-reforms-in-georgia-2004-2012/.

[27] “How to Increase Growth While Raising Revenue: Reforming the Corporate Tax Code,” The Hamilton Project,” Jan. 28, 2020, https://www.hamiltonproject.org/papers/how_to_increase_growth_while_raising_revenue_reforming_the_corporate_tax_code.

[28] Enache, “Sources of Government Revenue in the OECD.”

[29] Bunn, “Tax Policy and Economic Downturns.”

[30] Hannah Simon and Michelle Harding, “What Drives Consumption Tax Revenues?: Disentangling Policy and Macroeconomic Drivers,” Apr. 2, 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/94ed8187-en.

[31] Bunn, “Germany Adopts a Temporary VAT Cut.”

[32] “Guidance on the Temporary Reduced Rate of VAT for Hospitality, Holiday Accommodation and Attractions.”

[33] “VAT Gap,” European Commission, Sept. 13, 2016, https://ec.europa.eu/taxation_customs/business/tax-cooperation-control/vat-gap_en.

[34] “OECD Secretary-General Tax Report to G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors,” OECD, July 2020, http://www.oecd.org/tax/oecd-secretary-general-tax-report-g20-finance-ministers-july-2020.pdf.

[35] Elke Asen, “VAT Bases in Europe,” Tax Foundation, Apr. 2, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/vat-bases-in-europe-2020/.

[36] Daniel Bunn, Elke Asen, and Cristina Enache, “Digital Taxation Around the World,” Tax Foundation, May 27, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/digital-tax/.

[37] Leigh Thomas, “France to Impose Digital Tax This Year Regardless of Any New International Levy,” Reuters, May 14, 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-digital-tax-idUSKBN22Q25B.

[38] Aqib Aslam and Alpa Shah, “Tec(h)tonic Shifts: Taxing the ‘Digital Economy,’” IMF, May 29, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2020/05/29/Tec-h-tonic-Shifts-Taxing-the-Digital-Economy-49363.

[39] Daniel Bunn, “Digital Taxes, Meet Handbag Tariffs,” Tax Foundation, July 10, 2020, https://taxfoundation.org/us-french-tariffs/.

[40] “Special Meeting of the European Council – Conclusions,” European Council, July 21, 2020, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/45109/210720-euco-final-conclusions-en.pdf.

[41] Asen, “VAT Bases in Europe.”

[42] “Les Impôts de Production, Un Mal Français,” Institut Ḗconomique Molinari, June 10, 2020, https://www.institutmolinari.org/2020/06/10/les-impots-de-production-un-mal-francais/.

[43] Philippe Martin and Alain Trannoy, “Taxes on Production: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly,” Notes Du Conseil Danalyse Ḗconomique 53:5 (July 10, 2019): 1–12, https://www.cairn-int.info/article-E_NCAE_053_0001–taxes-on-production-the-good-the-bad.htm.

[44] William Horobin, “France Says No Tax Hikes as Nations Weigh How to Pay Virus Bill,” Bloomberg Tax, June 2, 2020, https://news.bloombergtax.com/daily-tax-report/france-says-no-tax-hikes-as-nations-weigh-how-to-pay-virus-bill.

Original Article Posted at : https://taxfoundation.org/global-responses-to-covid-19-pandemic/