Prospects for Federal Tax Policy After the 2020 Election

As Americans receive more clarity on the outcome of the 2020 presidential and congressional elections, the prospects for federal tax policy headed into 2021 are also becoming clearer. A Biden administration may have to work with a Republican Senate majority (pending the results of runoff elections in Georgia) and a Democrat-controlled House to navigate various tax policy issues in the coming year, including another round of pandemic-related economic relief and deciding what to do about upcoming tax increases built into current law.

One of the first priorities of a new Congress and a Biden administration is to revisit the economic relief currently being negotiated by the Trump administration and Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA). While there is a chance that a relief package could come together over the next two months, it is more likely that the next Congress and Biden administration will have to revisit this discussion and come to a compromise over core areas of disagreement. This includes the size and design of state and local aid, whether to extend more generous federal unemployment compensation benefits, and the potential size and scope of relief for businesses.

Policymakers will also have to decide whether to extend CARES Act provisions that expire at the end of the year, such as the removal of the penalty for withdrawing early from retirement accounts, if not addressed by the lame duck Congress and administration. There is also Democratic interest in providing relief through an expanded Child Tax Credit (CTC) or Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), proposals that President-elect Biden also embraced as part of his tax plan before the election. There will likely be debate over how germane such proposals are to pandemic relief, whether changes to those credits should be made temporary or permanent, and how those expansions would be designed to garner bipartisan interest.

Additionally, there are several tax extenders—temporary tax provisions that Congress can decide to renew—that will expire at the end of the year. These extenders include excise tax relief for brewers, wineries, and distillers and other industry-specific provisions. These extenders expire after an agreement at the end of 2019 to push many of them to the end of 2020.

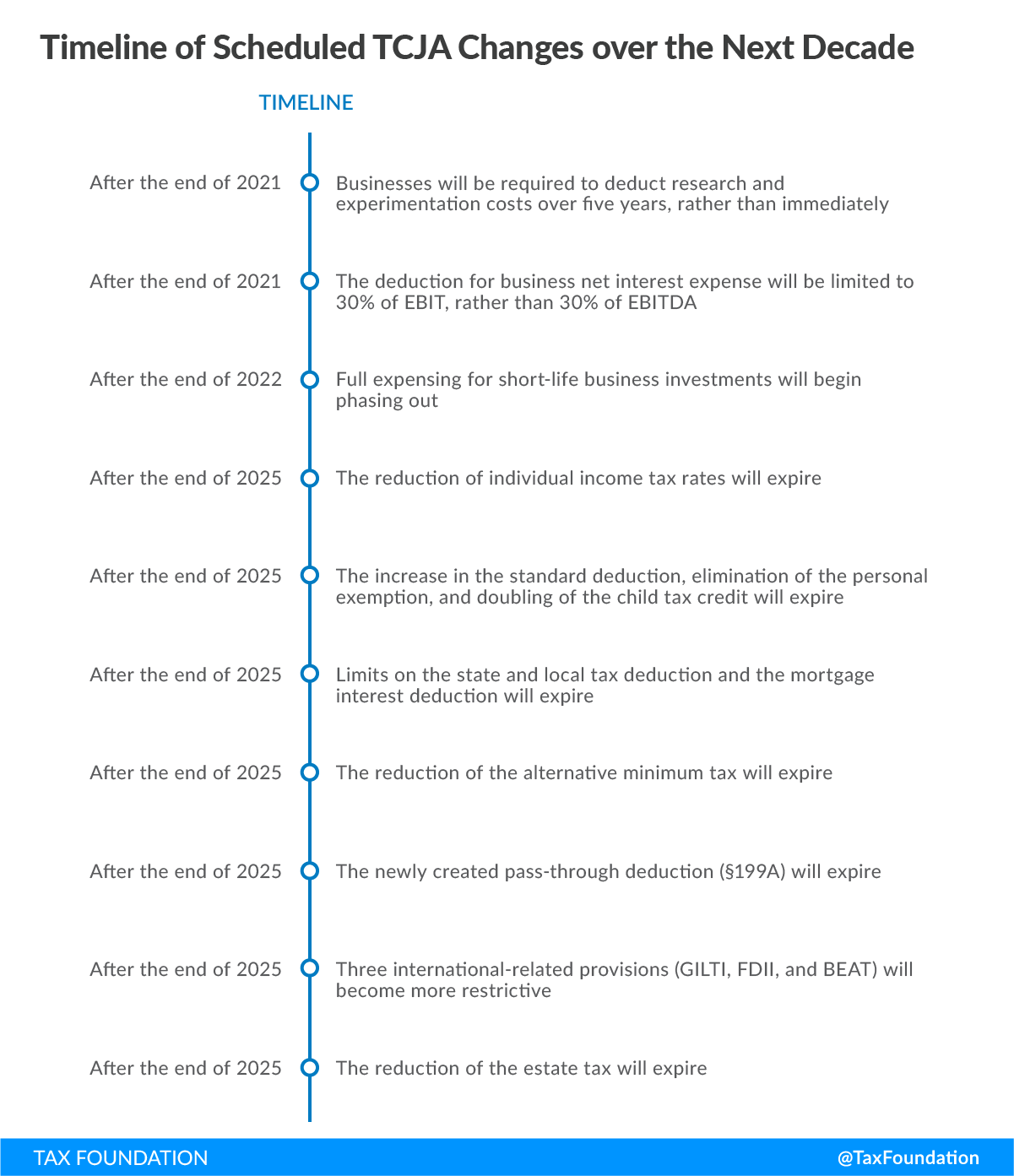

Federal policymakers will not just have pandemic relief and tax extenders to worry about next year. Starting at the end of 2021, we will see the beginning of the many tax policy changes built into the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). These tax changes will likely dominate the tax policy discussion over the next half-decade, as there may be interest from both parties to reform or repeal the tax changes built into current law.

In 2022, businesses will be required to amortize research & development costs over five years, rather than an immediate deduction that firms currently use. Lengthening the amortization schedule for R&D expenses would reduce investment and economic growth during a time when the economy is weak, while undercutting American R&D competitiveness. If policymakers cancel this upcoming amortization of R&D expenses, long-run economic output will be 0.2 percent higher and there would be about 47,000 additional full-time equivalent jobs, according to the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model.

In addition to the amortization of R&D expenses at the end of 2021, businesses using debt financing will face a tighter limitation on deducting interest expenses, moving from the current limit of 30 percent of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization costs (EBITDA) to 30 percent of earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT). This will raise the effective tax rate on debt-financed investment, and businesses that invest more could be at greater risk of hitting the threshold.

These two business tax changes are followed by a phaseout of expensing for short-lived assets starting in 2023. Making bonus depreciation of these assets permanent would increase long-run output by 0.9 percent, creating about 183,000 full-time equivalent jobs, according to the Tax Foundation General Equilibrium Model.

At the end of 2025, the individual income tax provisions of the TCJA expire too, bringing back a higher top individual income tax rate of 39.6 percent, a lower standard deduction, a return to the personal exemption, and a less generous CTC.

Ideally, policymakers would decide how to approach these upcoming tax changes in the years ahead and avoid temporary tax changes that kick the can down the road. This would help provide certainty for taxpayers and a better tax policy environment for business investment and economic growth. Preventing these built-in tax increases from undercutting the recovery should also be a priority.

Finally, the Biden administration will likely have to reconsider how to approach its sweeping set of tax proposals that increase taxes on higher earners. Biden’s tax plan largely depended on a Democratic sweep during the 2020 election. The current economic conditions make tax hikes an unattractive option in the short run, and a Republican-held Senate makes it less likely that there will be congressional interest in large tax increases.

President-elect Biden and Congress should concentrate on areas of common ground, finding incremental places to improve the tax code. A bipartisan bill recently introduced to help retirement savings is a good model for what incremental reform may look like. The 2020 election results suggest that compromise and incremental reform will be the most promising approach to make progress in tax policy over the next few years.

Original Article Posted at : https://taxfoundation.org/federal-tax-policy-after-the-2020-election/